Here’s What Really Sets Interest Rates (Not Central Banks)

See “powerful evidence that the Fed is not in control of interest rates”

Most everyone is familiar with the phrase: “Keep your eye on the ball,” which of course means — focus on what really matters.

Those who seek clues about the direction of interest rates believe the “ball” is their nation’s central bank.

For example, in the U.S., Federal Reserve announcements are the subject of countless financial headlines, like this one from Sept. 22 (Reuters):

Fed signals bond-buying taper coming ‘soon,’ rate hike next year

The assumption in most of these headlines is that the central bank determines the direction of rates.

However, if interest-rate observers kept their eye on what really matters, they’d be watching the bond market instead of the central bank. In other words, markets lead and central banks follow.

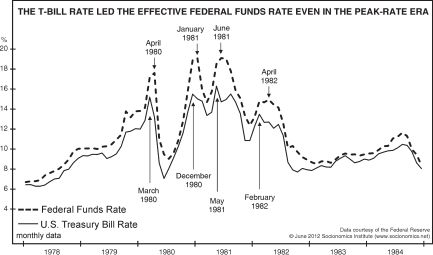

Sticking with the U.S., this chart and commentary from Robert Prechter’s 2017 book, The Socionomic Theory of Finance, provide elaboration:

[The chart] plots T-bill rates and the effective federal funds rate (a weighted average of the federal funds rate across all banking transactions) from 1978 to 1984. T-bill rates peaked four times in 1980-1982. Each of those peaks occurred a month or more before subsequent and reactive peaks in the federal funds rate. The Fed’s rate also lags at bottoms, as depicted on the chart at the lows of 1980, 1981 and 1982-3.

The book adds:

That interest rates were in a relentless upward trend during the entire decade of the 1970s and that they have been stuck at zero since 2008 — in both cases despite the Federal Reserve’s contrary desires — is powerful evidence reinforcing the point that the Fed is not in control of interest rates.

The same principle holds in other nations, like Australia or the United Kingdom.

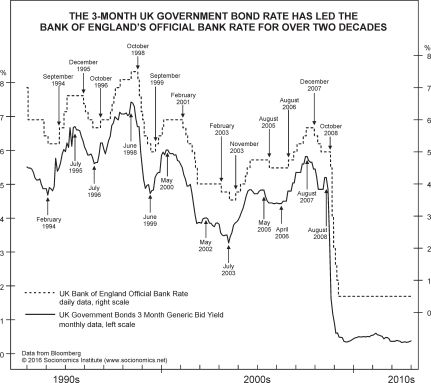

Here’s another chart and additional commentary from The Socionomic Theory of Finance:

[The chart] plots interest rates on the U.K.’s freely-traded, 3-month government bond against the Bank of England’s (BOE’s) official daily bank-lending rate. These lines show that the BOE’s rate-setting actions have lagged the freely traded debt market at all twelve major turning points in rates since 1993. The lags vary from two to nine months, and the average lag is 4.8 months.

The major takeaway is that central banks’ interest-rate decisions are not proactive but reactive.

Another widely held misconception is that news drives financial markets, like stocks.

Here’s insight on that pervasive assumption from Frost & Prechter’s Wall Street classic, Elliott Wave Principle: Key to Market Behavior:

Sometimes the market appears to reflect outside conditions and events, but at other times it is entirely detached from what most people assume are causal conditions. The reason is that the market has a law of its own. It is not propelled by the external causality to which one becomes accustomed in the everyday experiences of life. The path of prices is not a product of news. Nor is the market the cyclically rhythmic machine that some declare it to be. Its movement reflects a repetition of forms that is independent both of presumed causal events and of periodicity.

The market’s progression unfolds in waves. Waves are patterns of directional movement.

If you’d like to read the online version of this “definitive textbook on the Wave Principle,” you may do so for free once you become a Club EWI member.

Club EWI is free to join and allows members free access to a wealth of Elliott wave resources on financial markets, investing and trading — without any obligations.

Here’s the link to follow for free and unlimited access to the book: Elliott Wave Principle: Key to Market Behavior.